I wrote recent post about how the assumptions of the powerful often shape the questions that researchers ask about poor and working-class people. I asked at the end of that piece about how we know if research on first-generation students – most of whom are from poor and working-class families –asks the right questions about their struggles or if our research instead reflects the assumptions of more powerful people about them.

I talked about how first-generation student programming is primarily based on scholarship within the field of Student Affairs. Student Affairs staff on campuses have always done vital work to support individual students with counseling, tutoring, residential life, opportunities for career exploration and resume building, clubs for finding "my people" on campus and for developing leadership. This model of co-curricular work was built to support all students' well-being. It makes sense that they would now be working to fine tune those same approaches specifically for first-generation students.

It makes less sense to me that they're not yet developing new questions.

But it makes even less sense that Student Affairs is doing the work of first-gen support almost entirely without parallel work by faculty. Beyond the work of Student Affairs staff, students of color and women and LGBTQ students and students with disabilities also have access to faculty who, based on their identity and their scholarship, advise student advocacy groups, give campus lectures, and produce critical research that students read. At least until recently, faculty have advocated for a more inclusive curriculum and supported student spaces on campus explicitly focused on marginalized students learning to counter discrimination and to demand resources. Within classes and in co-curricular spaces, students from multiple other identities learn their histories, create art, plan events, and learn that college is preparation for speaking directly to power.

In contrast, first-generation students learn be more assertive in seeking help for their weaknesses and to gratefully listen to mentors and advisors.

Research into how social class and educational inequalities shape the experiences of poor and working-class students is rare. When faculty are present in projects such as the annual First Generation Celebrations, it's most commonly in the role of inspirational mentor. In years of following reports of those celebrations, I've yet to see faculty sharing scholarship on campus obstacles to the success of first-generation students or on deeply unequal K-12 schooling experienced by the students on campus. Even student advocacy groups organized around other identities can be hostile places for poor and working-class students, but students seem to be left on their own in navigating those tensions.

We've been through a year now of devastating cuts to funding for the schools, social safety nets, health care, housing, and food supports within poor and working class communities. College access programs, community college funding, research funding that enabled first-generation students to go to graduate school, all have been slashed at the hands of one of the wealthiest administrations we've ever had, all while those powerful people often publicly denigrate low-income people as lazy frauds. Everyone on campus is hearing those messages about who is and is not deserving.

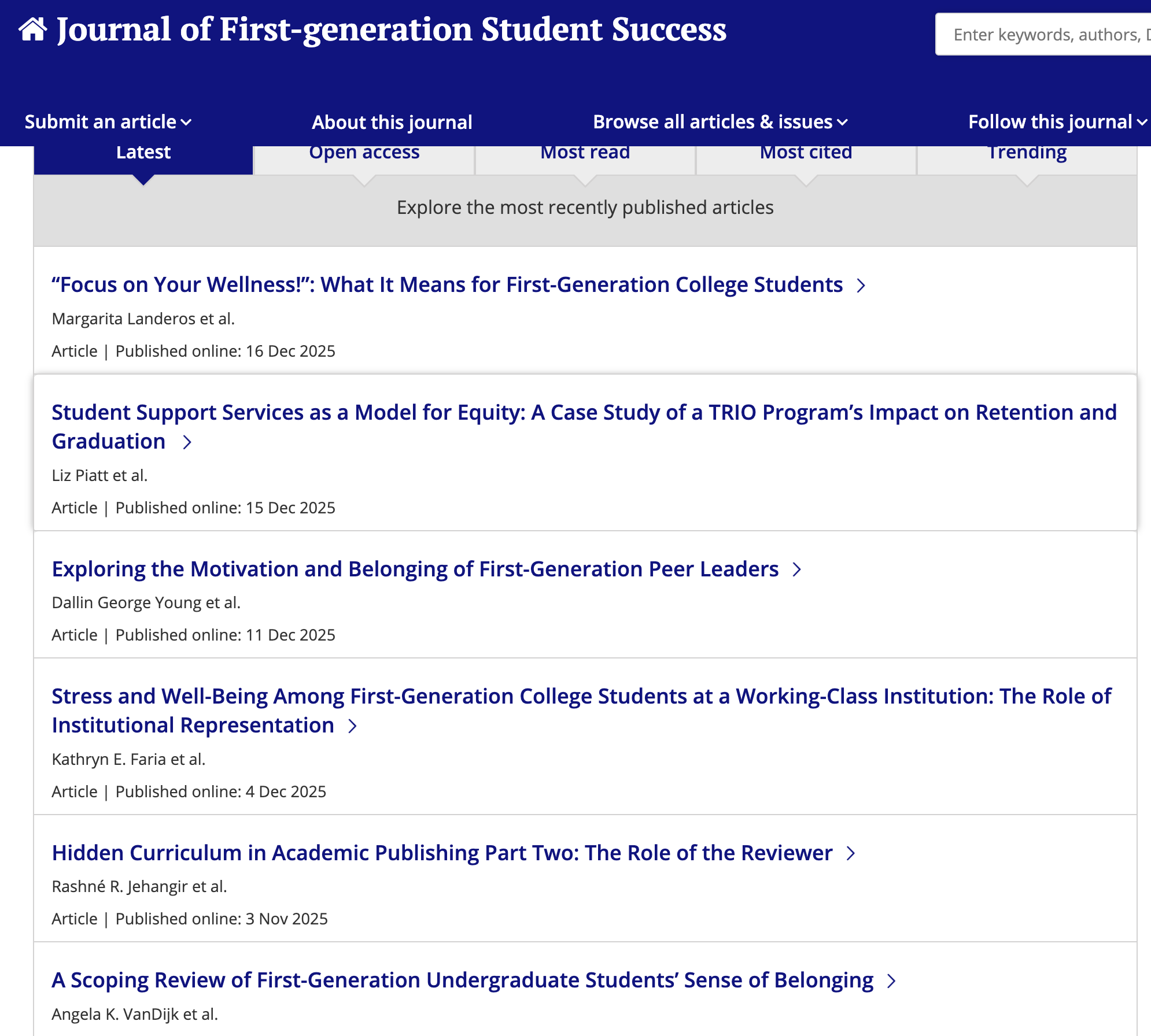

At the end of that year, the flagship journal of First Gen Forward, the group that coordinates most first-gen programming on campuses, is pursuing essentially the same research questions about refining supports for individual student self-improvement that they've asked for years.

And it can be very difficult to find faculty in sociology, education, or other fields doing research on how campuses might also support campus critique of social growing class inequalities and classism. I have seen no instances (and I'd love to learn about what I've missed) in which faculty work with first-generation students to ensure that they are learning the citizenship skills of critique and collective voice. I've seen nothing about this being a critical moment for powerful people on campus to name and decry casual and intentional classism.

What if we're asking the wrong questions about what else poor and working-class students need beyond the well-intended and ever-more refined support for their personal development?