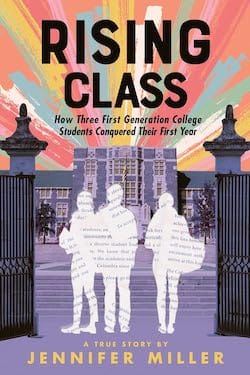

In Rising Class: How Three First Generation College Students Conquered Their First Year, Jennifer Miller writes of Briani (a Latina from Georgia) and Conner (a white male from rural Missouri) who enroll at Columbia, and Jacklynn, Conner's girlfriend, who begins college at a community college near home. All are low-income first-generation college students. Briani and Conner were supported by QuestBridge, a highly competitive program for high-achieving students from low-income families. Jacklynn chose not to apply to QuestBridge to instead stay closer to home and family.

Of all the books I've read on first-generation/low-income students, Miller most vividly locates the students within overlapping social worlds that are each stratified by race, class, and gender. As she follows them through their first year of college, she makes clear that we can only understand these students by also understanding the social systems that work against their success.

Rising Class is marketed as Young Adult non-fiction but I never thought of this while reading. The book would be an excellent read for undergraduates – and those who advise and support them. Miller, a journalist, shadowed the students in their home towns and on campus, talked with them often, met with friends on campus friends and back home, and came to know their parents.

Briani and Conner were outstanding high school students whose high schools offered AP and International Baccalaureate programs. They embrace the intellectual culture of Columbia (though they marvel at how little their wealthier peers study as they work constantly to keep up). They're acutely aware of the ease of their peers' lives: The casual talk of summer travel and second homes, the branded clothing, the ease of joining any extracurricular activity without worrying about fees or conflicts with work hours, the limitless spending money sustaining their social lives. Their peers can choose any major that will make them happy. Briani and Conner and Jacklynn are deeply aware that they need to choose majors that will allow them to support themselves as soon as they graduate and to also help their families. They are clear that they have earned their place in college but that "college" is a very different experience for their wealthier peers.

Family

Miller writes about the students' relationships with family with much more nuance than I've seen in much of the literature about first-generation students, perhaps because she met and spoke with the families and came to know their communities. All three students are deeply entwined with the lives of their parents, and all are deeply aware of how precarious their parents' lives have been.

These family ties are deeply emotional and also deeply material. Briani's immigrant parents run a restaurant and work long hours just to break even. Conner and Jacklynn's single mothers lives were constrained by low-income jobs, pervasive stress and anxiety, partners' addiction, and too few safety nets for getting through any of this. These students worked shifts to help out, provided parents and siblings emotional support during family crises, helped family to navigate agencies that seemed indifferent to their needs. All of the students understand that their role in their families is an indictment of structural inequality, not of their parents.

These students and parents love each other, and all three students grapple with what it means to love struggling family while seeking a different life for yourself. The parents are proud and supportive of their children, yet they have no replacements for the roles that their children played in meeting the families' material needs. So much of the literature on first-generation students implies that students struggle to separate from their families. These students are, instead, separating from the limited opportunities of their communities while working very hard to remain close to families.

There's no mention anywhere of Briani, Conner, or Jacklynn finding anyone on their campuses who can offer resources when parents face crises or who will even simply listen to what it means to love parents who need their savvy children to help them navigate their daily challenges of lives with too few options.

The Isolation of Social Class

Briani and Conner negotiate their own constraints – Conner goes back to his dorm room after a debate club that he loves instead of joining others at a social gathering that he can't afford. Briani wants to embrace all that New York has to offer yet makes the most of a special night out with friends on a budget of $20.

Briani aspires to be a journalist, a major reason for her choice to attend Columbia, yet learns at the first orientation for those who will apply to work on Columbia's excellent student newspaper that the expected workload (with a stipend, but at minimal pay so that she'll have to find a second job) will be almost impossible for her. She does eventually interview for a position and realizes, only later, how the screening questions are unfairly skewed to students who grew up in families with leisure time and money for magazine subscriptions. She also learns only later how few of the student editors are even on financial aid, let alone needing to work extra jobs to afford the privilege of working on the paper that will open career paths for them.

Meanwhile, Jacklynn lives between the comfort of familiarity and a growing restlessness to to become someone she has not yet imagined, even as she deeply values her relationship with her mother. She does well in her courses, but isn't clear if the courses are easier than Conner's or if she actually is a good student. She's clear that she's preparing for a career, not experiencing a rapidly expanding sense of the world as Conner is just in living in New York.

While the literature on first-generation students stresses the importance of "belonging", the students are isolated from peers by money. Mentoring students to more assertively network and to join clubs is good; providing them the financial support that eases the burden of doing so is even better.

By Spring, Columbia sends students home as COVID intensifies and Briani and Conner are now studying and attending online classes in their childhood bedrooms. Now, they face the expenses of storing their belongings, finding reliable internet in their home communities, and finding jobs during COVID to cover their expenses. They are hanging again with high school friends, sharing meals with families.

So much of the literature applauds first-generation students for their resilience without showing us the lives of actual students in the complex social spaces of home and campus. Miller's book shows us the lives of students too often invisible on campus, making clear the costs of years of having to be so "resilient".