Later, she'd go on to write the book Maid and that memoir of cleaning privileged people's houses as she raised her daughter in poverty was optioned to become a popular Netflix series.

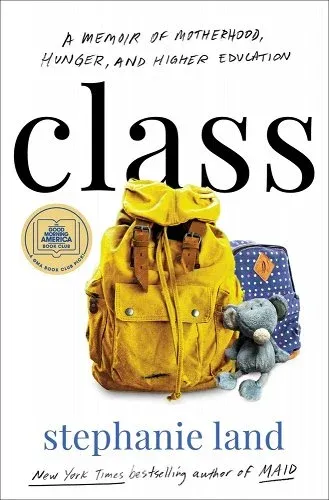

But before she wrote Maid, she was navigating college as a single mother in her thirties who struggled not only with homework but with the endless bureaucratic hurdles of food stamp programs, child support enforcement, financial aid, child care, and unarticulated academic program expectations. She writes about all of this in her second book, Class: A Memoir of Motherhood, Hunger, and Higher Education.

With a life-long dream of being a writer, Land believed that a college degree would finally lead to a stable career. She embarked on what she understood to be a socially-valued project of self-improvement. She moved to Montana to transfer to a well-regarded English degree program after first attending a community college. She does exactly what so many traditional college students take for granted, but for Land, college is an endless reminder of her economic precariousness within broken social systems.

Things go wrong immediately: Only after she arrive in Montana does she learn that she'd have to pay out-of-state tuition, that house cleaning jobs pay much less than her clients back in Washington, and that child care options are painfully limited. From there, Land navigates "disaster always breathing down my neck" as she works to complete her junior and senior years of college.

She writes of depending on a car that starts only sporadically ("my car not working never felt like anything less than a personal failure"), on food stamps for the meager groceries in her refrigerator (her qualifications constantly threatened because she's in a degree program, not vocational training), on a series of roommates for who offer childcare in exchange for rent, on rare kind staff who bend rules so that she afford summer camps for her daughter, on friends who sometimes take her child camping for a weekend so that Land can carve out rare time for friends and college essays and sleep, and on impatient staff assigned to help her to unravel the legal maze of enforcing child support orders across state lines. Little in the formal system supports her goal of completing college.

While she struggles to fulfill the American dream of a college degree and then economic security, she writes vividly of the exhaustion and shame of it all, keenly aware that she was expected to be grateful for every bit of assistance that she received or risk losing it all:

It was easier for a lot of people to imagine how strong and high-functioning I was, as opposed to how desperate and on the edge of disaster we actually were.

To change our society’s worship of the concept of “resilience” would require a whole other way of thinking. But that’s unlikely to happen, not when there are whole systems in place to keep low-wage workers so desperate for paychecks that they’ll do all the jobs no one else wants to. Not when it would require trusting poor people with money for food without making them prove they worked their asses off for it.

Resilience is a flag we poor people could wave to gain that trust. If we proved ourselves time and time again—if we pulled up those f— bootstraps so hard they broke and our response was to shrug it off before we found some way to fix them so we could immediately start pulling again—people nodded in approval. They might even have assigned us to the “deserving poor” line when we needed more than what was offered. But if I told people about the debilitating panic attacks that sometimes took hours to recover from?

Some of her faculty are deeply understanding when she needs to miss class to wait for phone calls from child support lawyers or when she badly injures herself but can't go to the ER because she has no health insurance. Some welcome her child to classes when child care arrangements fall through at the last minute and some explain to her how to approach faculty for support. Yet others stand in judgment of Land's tattoos and clothing as "not professional" and act as gatekeepers to the professional networking available to other students.

She has to beg her child's school not to keep punishing her kindergartner for being late to school when being late is about too little sleep, that unreliable car, and tantrums over too little food for breakfast. She begs her father for help at a critical moment but he never calls her back. She struggles with how little mentoring she gets in her program about how to break into free lance writing and learns late in the game that at least some of this insider information is shared at program social events that she cannot easily attend.

She knows that her daughter's well-being depends upon always being perceived as "deserving poor", and then experiences profound consequences for slipping in the same ways that thousands of other college students slip every year: an unplanned pregnancy subjects her to yet more bureaucratic struggle and more judgment (and self doubt) over whether she is worthy of admission to graduate school in her department. She writes honestly of her choice to keep the baby, even as she knows that that decision will justify dismissal of her broader story by those with power over her as being not about a broken system but about a poor (and therefore questionably moral) woman who just didn't want success badly enough.

When so many poor and working-class students are held up by their campuses as evidence that the system is fair and welcoming, Land writes vividly of what so many of those students feel that they need to hide. Few of her peers or program faculty and staff knew how deeply stressful it was for Land to fight the layers of bureaucracy to simply stay in school. Land explains that she wrote the book in part so other poor parents trying to get degrees know that "it's not your fault that it's hard". With 28% of first-generation college students being older than 30, many students stand to benefit from hearing this.

In writing for these students, Land claims her right to anger with punitive systems disguised as support while also understanding that her whiteness provided a level of protection:

I sound angry, don’t I? I hope I do. I’ve spent so much of my life pretending not to be angry, and I’m not doing that anymore. And I don’t even have as much to be angry about as a lot of people. I’m deeply aware that while our poverty put Emilia and me squarely in a marginalized group, our whiteness gave us camouflage. Because of our white skin, we weren’t immediately assumed to be poor and then treated poorly as a result. No one other than the grocery store clerks knew that I needed food stamps to afford staples. No one other than caseworkers offered me the left-handed compliment of noting how “well-spoken” my daughter and I were. I got the occasional break from my poverty, at least in terms of its visibility to others. In terms of how it felt inside, the constant, crushing panic? I never got a break from that.

Years ago, Stephanie Lawler wrote of how poor and working-class women who bring their lives to middle-class educational institutions have their very sense of themselves and their relative worth in the social world questioned within the dailiness of academic life:

class relations are not just economic relations but also relations of superiority/inferiority, normality/abnormality, judgement/shame. But the apparently personal, private pain which these relations engender is a manifestation of political inequalities.

In adulthood, after finding fame and a measure of financial security through her writing, Stephanie Land finally wrote of the political inequalities beneath the weeks and months of crushing poverty, judgment, and shame that she endured while she was in college.

We might wish that college staff would learn from her story, would invite more students to speak earlier of the political inequalities that shape their lives, and would then leverage the collective intellectual and political resources of higher education to address those inequalities. Applauding students for their "resilience" without inviting their stories about why they've needed to be so resilient in the first place will never serve any student well.