When I taught elementary school in southern Appalachia early in my career, none of the very low-income children in my classes had telephones at home. In the time of landlines, telecom companies had not yet found it profitable to run trucks and wires up the steep and poorly-maintained rural roads to provide service. School staff couldn't call home in emergencies, to check on absent children, or even just to partner with parents on their kids' learning.

In 2025 many poor and working-class children have been denied reliable access to the internet. The issues are similar to what my students in Kentucky faced years ago: Phone (in the olden days) and internet were/are both typically provided by monopolies in any given community. Private companies want to maximize profits, and it's more lucrative and convenient for them to invest in higher-income communities while ignoring other neighborhoods (or providing only shoddy service for higher fees).

Many us remember the images that we saw of children trying to connect to the free wifi in fast-food restaurant parking lots during COVID school closures. Early in the pandemic, nearly a quarter of low-income parents reported that their children had to find public wifi (outside of shuttered public spaces) to finish school work because of lack of access to the internet at home. Even more low-income parents reported that their children could do homework, but only on cellphones with data plans. Schools scrambled to get mobile hotspots and laptops out to families, but these were unreliable stop-gaps, not permanent remedies to digital divides. First-gen college students sent home during campus shut-downs were similarly deeply frustrated by slow and spotty internet in their home towns as they tried to finish courses.

How Deep are Digital Divides?

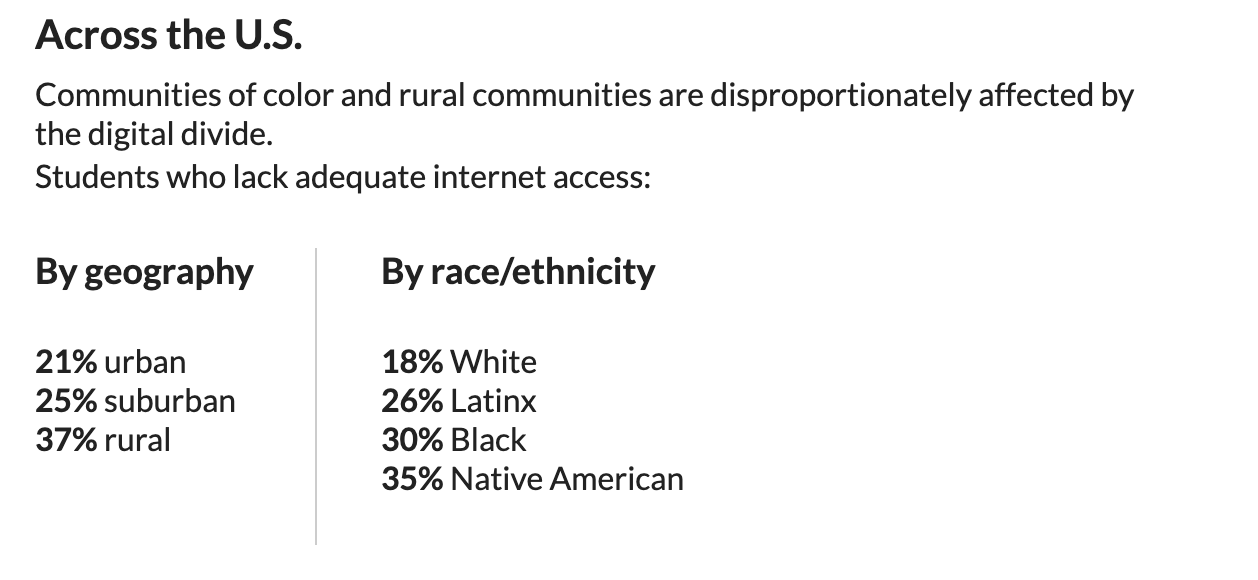

Common Sense Media has documented how extensive these digital divides still are for students and for teachers living in communities where Internet Service Providers have still not provided basic, affordable service. 16 million children and 400,000 teachers lack adequate internet to support remote learning:

Common Sense's excellent interactive map offers data on digital divides for each state along with stories from teachers about how these gaps affect them and their students. In nearly every state, nearly a quarter of students lack adequate home internet access; in too many states, it's closer to a third of all students; in some states it's more.

So What Can Be Done?

The Biden administration included funding for expanded broadband access in the Infrastructure Bill, and the FCC then went through the lengthy rules- making process to outline how, with federal support, Internet Service Providers would be required to end "digital redlining" and to stop discriminating against low-income neighborhoods and communities in both access and the fees charged. It was only a start, but a good start. Industries sued, and the Biden DOJ was defending the Digital Discrimination rules through appeals when he left office.

Trump's administration declared an end to all "diversity equity and inclusion" endeavors. The new FCC chair has dissolved the Digital Discrimination Task Force created to oversee implementation of the new rules. He declared that because of "equity" in language about inequitable access to the internet, the project the now forbidden as "DEI". Technically, the Digital Discrimination FCC rules are still in place since the funding was allocated by Congress and the rules were passed through formal mandated process, but there's now no accountability it's doubtful that the new DOJ will defend the rules against industry's court challenges.

I accept that there are different political perspectives on how we achieve educational equity. You may believe that "market forces" will eventually get all communities access to the internet sometime in the future. You may instead believe that the government has a rightful role in requiring companies profiting from monopoly control of internet markets to invest some of those profits in providing access to all communities. You may believe that it's the role of philanthropy to support low-income people, at the discretion of the philanthropists.

But the point is that as of now, none of this is happening and there's no sign of any pathway for more students to get access to what is now a basic resource for learning, getting information about local emergencies, applying for jobs, or communicating with those supporting our well-being from health care providers to those providing social safety nets.

"Resilience" in the Face of Structural Inequalities

Campuses often celebrate the "resilience" of first-generation college students without ever saying much about why they needed to develop resiliency as children (beyond parents being unable to advise them about campus culture). Just one of the things that has required "resilience" is when young students are left on their own to find ways to connect aging laptops to scarce public wifi to complete school assignments, all while knowing that students in other communities were blazing along on high-speed connections.

Free cupcakes in recognition of first-gen/low-income student "resilience" are great. (I love cupcakes. Chocolate, please). And I also deeply appreciate it when those with more power work to break down any of the many structural economic barriers that so many families face. In the meantime, I want campuses to be very transparent about the why of "poor and working-class students first-generation students often struggle", because otherwise, the simplest answer is that students themselves are deficient (though "resilient").

I want campuses to not leave it students themselves to have to explain to their peers – and faculty– how they had to sit in the parking lot of the closed public library to grab wifi, but the connection was still so spotty that they missed a lot of calculus class. I want students to not have to confess these things as personal oddities rather than as structural social class barriers affecting 16 million children in the U.S.

Reliable internet is just one of the structural barriers against the success of students from poor and working-class students.

Whether you believe that "the market" will eventually solve this, whether government should be part of equalizing opportunity when markets will not, or whether you imagine philanthropy filling the gaps of both, no one seems to be doing anything right now, and the power to change this lies primarily outside of poor and working-class communities.

We can recognize the "resilience" of students in ways that doesn't only place responsibility on them to personally overcome the indifference of private companies, governments, and philanthropists. We can and should also bring other voices to advocate for them across all those sectors.

But first, campuses have to make those structural barriers visible. Framing poor and working-class students as facing vague personal "challenges" is not enough.