When I first moved to Seattle, I made the rounds of multiple school districts that would be partnering with our new teacher education program. In one of the first elementary school classrooms I visited in an aging urban school building, a custodian was duct taping cable along the baseboard so that two computers in the back of the classroom could connect to the internet. My host was clear that the connection would be slow and sporadic, but kids would have at least some access to "technology".

When I got back to campus and told this story to some staff members, one told me that in her district, an elementary school nearest the offices of a major technology company was installing a brand new computer lab with room for an entire class to work. Not only did the school have extra space for a lab (a rarity in a rapidly growing region), but a parent was donating all of the PCs and software.

The Washington state constitution declares

It is the paramount duty of the state to make ample provision for the education of all children residing within its borders, without distinction or preference on account of race, color, caste, or sex.

Yet in the decades that I've lived here, there have been multiple law suits over funding, annual intensive lobbying of the legislature, teacher strikes, and reports by public education advocates on the persistent budget shortfalls and inequalities within and across districts.

The latest of these reports was just published by The League of Education Voters.

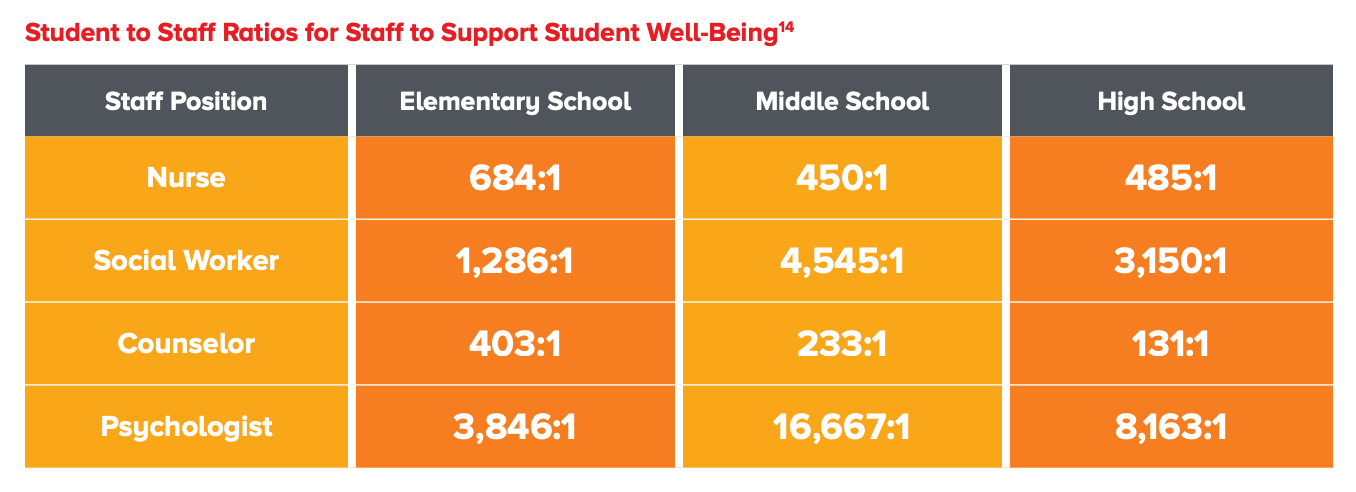

They argue persuasively that as schools welcome children who face growing challenges – mental health, physical health, family crises, failing social safety nets, and the aftermath of a deadly pandemic – staffing to support students has stagnated. The caseload of support workers in Washington schools is stunning:

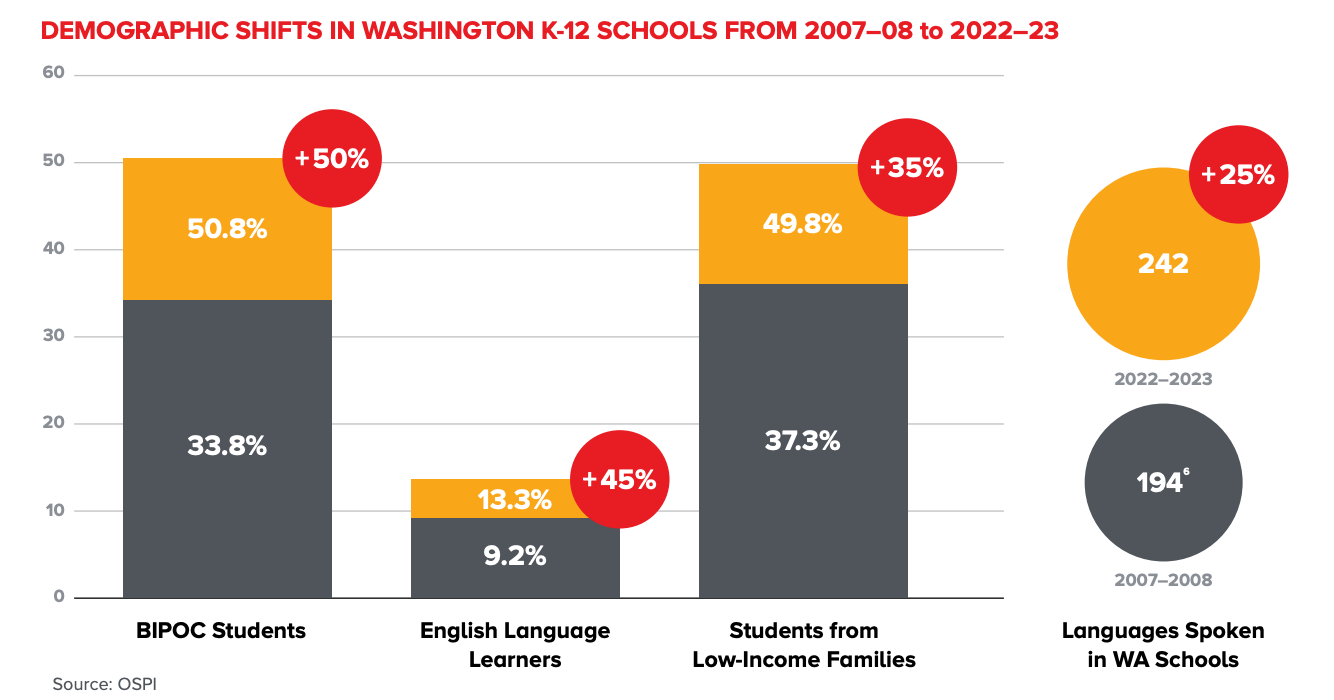

Funding models are not keeping up with a nation-wide diversification of the student population, and the consequent need for teacher professional development, paraeducators, and specialized teachers. The parents of low-income students often benefit from partnerships with schools in which teachers have designated time for conferences and communication, social workers help to connect families to social services, and parents have access to events and activities through which they can learn how to best support their child's academic work:

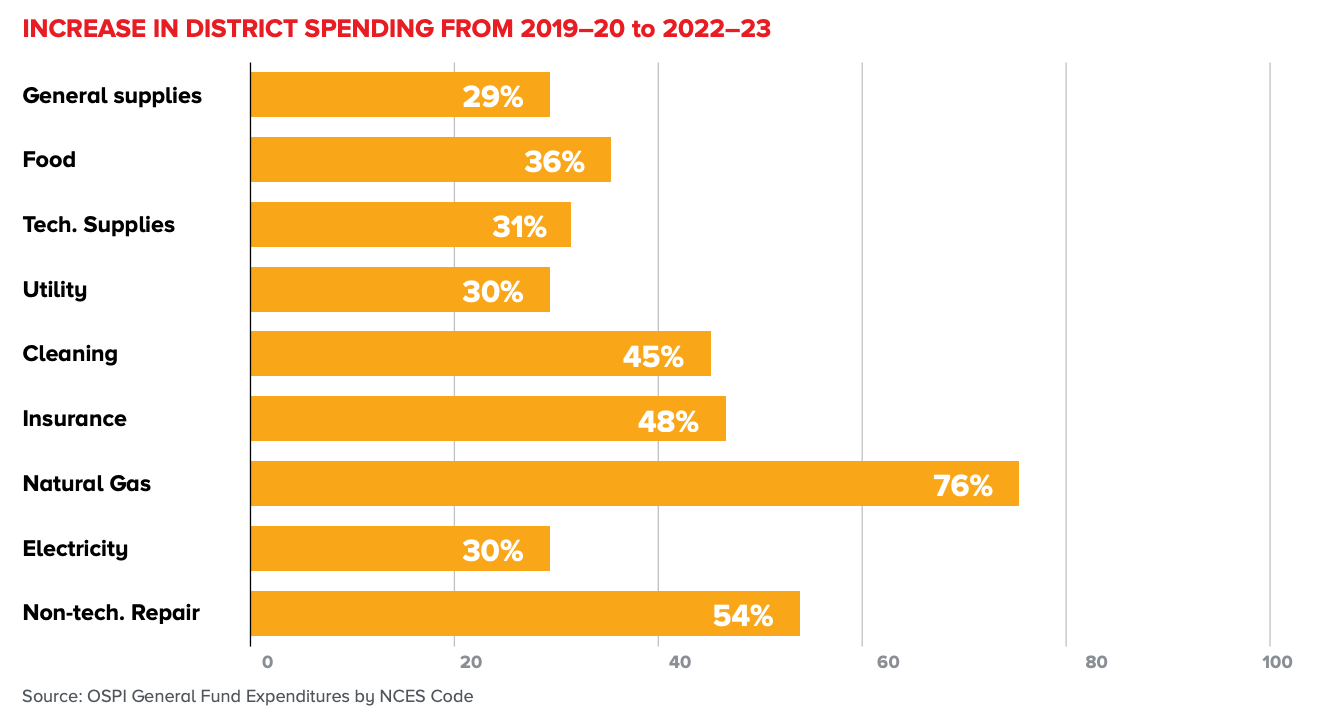

And the cost of everything is going up.

School funding is a matter of political will. Support for school funding diminishes in areas in which people define education as a private rather than a public good. Suport for school funding diminishes in communities with aging populations Support for school funding diminishes when wealthy parents are buffered from the effects of budget shortfalls.

In one district near my campus, the PTAs of schools in the wealthier northern suburbs would hold elaborate, competitive fundraisers every year. The parents would donate and auction bottles from their wine collections, weeks at their vacation homes in Mexico, perks from their businesses and tables at wonderful restaurants.

How did they spend the tens of thousands of dollars they'd raise? One school hired a science specialist so that classroom wouldn't have to teach science. Another school, alarmed that average reading scores had dropped a few percentiles points lower than a neighboring school (they were both within the 90th percentile) hired a reading specialist to work with the few kids lowering their averages. They bought art supplies, technology supplies, field trips, and adventure playground installations. All just for their kids.

A principal friend in the south end of the district would laugh that she was thinking of writing a grant to ask for some of their funds to help to support her students who were low-income English language learners and the children of service workers who lived in apartments. They didn't have vacation homes or wine collections to auction to support the school; did couldn't dream of having the money to even think of bidding on such things.

In Washington and in many states, school have to go to voters to pass bonds to fund school repair or construction. Some districts try to win these elections over and over for decades as roofs leak and teachers hand out blankets to cold students. Nationally, public schools have documented tens of billions of deferred maintenance on aging buildings.

And of course, the costs of these budget shortfalls fall disproportionately on poor families in districts with too little to tax and too little political power to sway the legislature to invest more in the education of their children.

It's hard to square the belief that doing well in school will level playing fields when funding for schools is far from level and far from adequate in too many places.