Harvard's Opportunity Insights team and the Census Bureau have collaborated on a powerful Opportunity Atlas that analyzes – at the neighborhood level – very unequal childhoods. The researchers analyzed multiple neighborhood variables and income at age 35 for 57 million children born between 1978 and in 1992. They sought to better understand why children from some neighborhoods were able to attain economic mobility as adults while children from other neighborhoods did not.

Users can search by city, zip code, or county and compare median household incomes by race, family income, ethnicity, and/or gender. We learn a great deal about each neighborhood and community: Employment rates, household and individual incomes, the distance of commutes for workers, incarceration rates, the number of children raised by single parents, the percent of children who stay in the tract as adults, average rents and job gains/losses.

There is a lot of data, in graphic form, with multiple explanatory links and help buttons to assist with interpretation.

All of this was built to analyze "the relationship between the places children grow up and their incomes in adulthood". They found abundant evidence that "success" is about so much more than individual motivation and resilience. Growing up in thriving communities with high employment and among healthy adults "dramatically improves children's outcomes", regardless of family's own circumstances or even above and beyond where children eventually live as adults. Growing up among adults who can support themselves at work, who have access to social safety nets and whose local governments support their well-being matters in childrens' sense of their place in the world and their knowledge of the world beyond where they live.

Yet fewer children are growing up in such places.

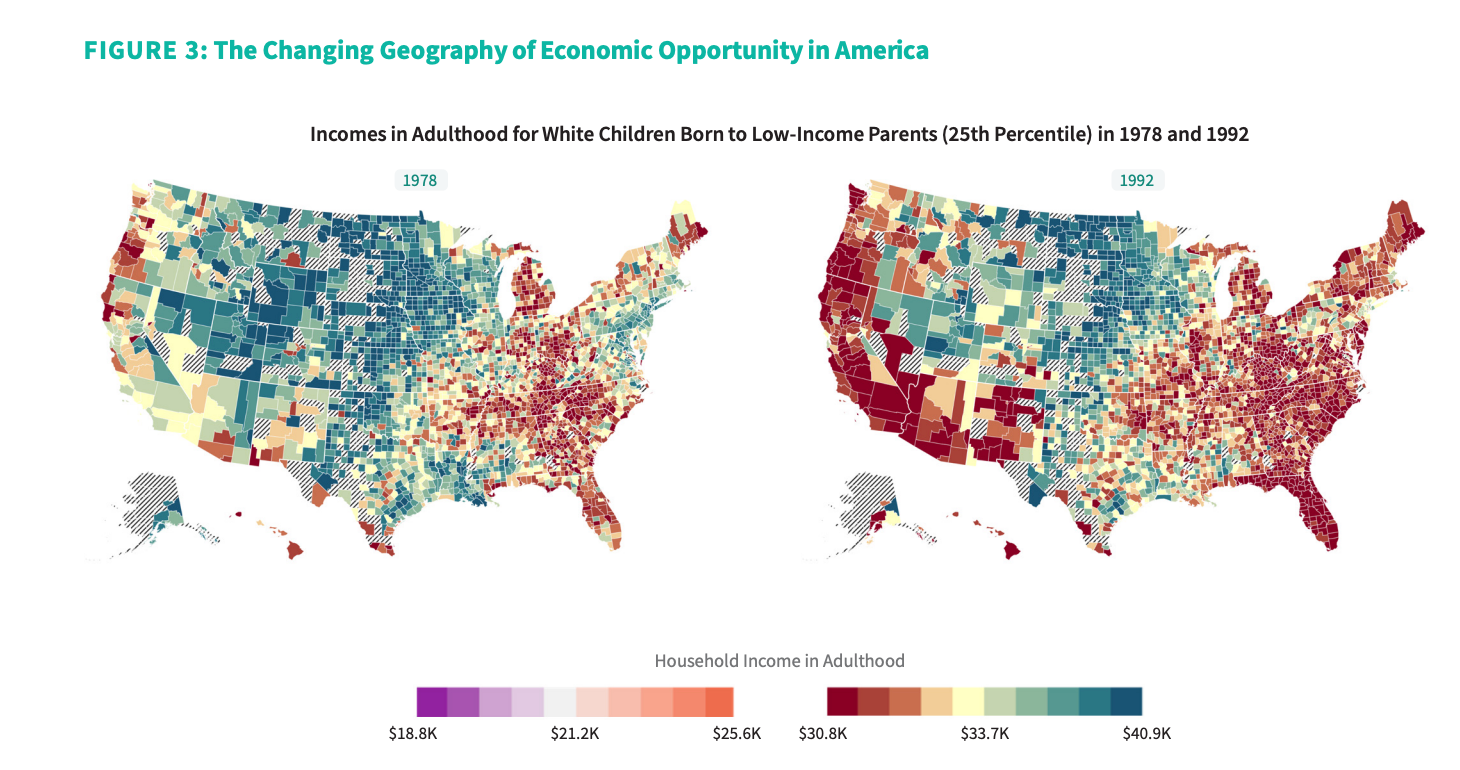

The shift is evident in these maps of the adult income of children born to low income parents in 1978 and then in 1992. First, the maps for white children:

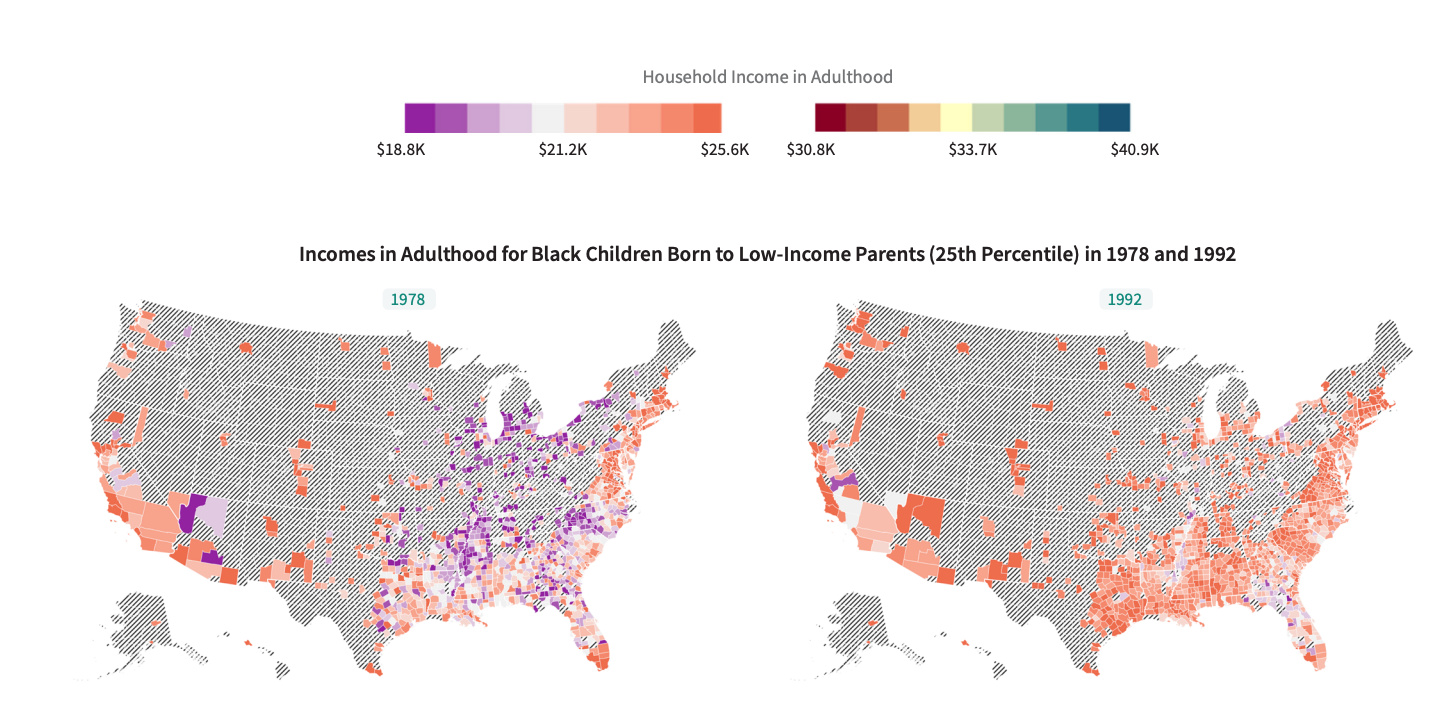

And the maps for Black children.

The site includes stories of initiatives in select cities to level playing fields. The Seattle story, for example, explores a project in which families were given vouchers to live in neighborhoods with higher mobility rates. User can toggle, for example, to find "opportunity bargain" neighborhoods in the region with affordable rents (with vouchers) where children experience relatively high rates of mobility. Families' values and aspirations didn't change in these new neighborhoods. Children's access to social networks and educational resources did change.

The project is summarized in the authors' [non]technical report, Changing Opportunity: How Changes in Children’s Social Environments Have Increased Class Gaps and Reduced Racial Gaps in Economic Mobility (more technical data analysis is also available at their website). While large racial gaps persist, class gaps are growing for white children:

White children born to low-income (25th percentile) parents in 1992 grew up to earn less on average than white children born to low income parents in 1978. Over this same period, income increased for white children born to in high-income (75th percentile) families. These divergent trends resulted in growing class gaps among white children. The gap in average household incomes for white children raised in low- versus high-income families grew by 28%, from $10,383 for those born in 1978 to $13,202 for those born in 1992 (Figure 1).

For Black children, incomes in adulthood increased across all parental income levels. As a result, Black-white race gaps in economic mobility shrank. The gap in average household incomes between white and Black children raised in low-income families fell by 27%, from $12,994 for children born in 1978 to $9,521 for children born in 1992.

It is not possible for highly stratified schools and colleges to erase the effects of unequal childhoods in economically segregated communities, regardless of our joy in applauding those who do – with a great deal of luck and personalized support – find a measure of economic stability through formal education. The authors argue (and demonstrate, in their stories of opportunity) that investments in the social and economic resources in communities in which low-income families raise children are long overdue.